UK government aims to kick start next-gen nuclear

The British government has begun Stage 2 of its Advanced Modular Reactor (AMR) competition as analysts and companies warn challenges remain for next generation nuclear in the country.

Related Articles

The competition forms part of the AMR Feasibility and Development (F&D) project by the government’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) which aimed to invest a total of 44 million pounds ($56 million) to “kick start next-gen nuclear technology”.

Phase 1 spent 4 million pounds to undertake feasibility studies for AMR designs while Phase 2 has shared 30 million pounds between three selected companies to continue with development work and the remaining 10 million for smaller research, design and manufacturing projects.

“Today’s investment will immediately create new jobs in Oxfordshire, Cheshire and Lancashire. But through this vital research, the technology could also create thousands more green collar jobs for decades to come,” Minister for Business and Industry Nadhim Zahawi said in a statement while Prime Minister Boris Johnson also reiterated the country’s commitment to nuclear during a recent PM’s Question Time.

Some 10 million pounds was granted each to Tokamak Energy, Westinghouse and U-Battery.

“This announcement is fantastic news … and kicks off just under a couple of years or so of our engineering work. It’s important because it sends a very strong signal that our host government (in the UK) is supportive and that we’re aligning well with the UK national interest,” says U-Battery Director of Government of Affairs Chris White.

U-Battery is developing an advanced, small modular reactor and it plans to initiate the next phase of design and development work this year followed by a first-of-a-kind commercially viable reactor by 2028.

The government award was a major milestone for U-Battery as it continues to advance its dual-track market development efforts to bring its advanced SMR technology to the UK and Canada, added Steve Threlfall, General Manager of U-Battery.

“From the government side we’re hoping for guidance on items such as siting and planning. Those are the things we’ll be looking at falling in to place as we come on the flight path to our first of a kind,” says White.

Westinghouse meanwhile is developing a lead-cooled fast reactor while Tokamak Energy is the odd-one-out of the group as the only company not working on a fission nuclear reactor but rather are concentrating on fusion technology.

Potential nuclear capacity to 2050 in the UK, "Forty by '50: The Nuclear Roadmap" (Source: Nuclear Industry Association)

Potential nuclear capacity to 2050 in the UK, "Forty by '50: The Nuclear Roadmap" (Source: Nuclear Industry Association)

Large Reactors

Without the procurement of new nuclear build, the UK nuclear fleet will likely shrink to 3.2 GW after the shutdown of Sizewell B in 2035 (assuming its life is not extended) and as the country’s Advanced Gas-Cooled Reactors close with only Hinkley Point C, currently in construction, remaining operational.

A lack of government support has prompted nuclear projects in Moorside and Wylfa Newydd to be abandoned or put on hold while companies such as RWE, Eon, Centrica, GDF Suez and Toshiba have also given up new nuclear build plans in the UK.

According to the Energy Systems Catapult (ESC), an independent research group, using their Energy Systems Modelling Environment (ESME) tool, a commitment by the government to a further 10 GWe in large reactors, beyond Hinkley and on top of any Sizewell extension, would be a decision of low or no regret.

The study noted costs need to fall significantly if the technology is to fulfil its long-term potential.

The initial costing of large, gigawatt-sized nuclear power stations can be prohibitively expensive. Since the infrastructure alone can take up to ten years to build before a single kilowatt is generated, investors expect to be compensated for the wait with the cost of capital representing between a half and two-thirds of a total nuclear project.

“This is nationally critical infrastructure, with assets that are going to last 80 to 100 years and that requires a bit of impetus. You need a lot of money up front and, without the government’s backing on financing, the costs go up and up because you’re borrowing money at market levels rather than government rates,” says Head of Policy & Public Affairs at the Nuclear Industry Association (NIA) Ieuan Williams.

In July last year, the government launched its Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model whereby investors would receive regulated returns and so reducing financing pressures, though it has yet to be deployed.

“The AMR competition result is very welcome, but there’s a raft of announcements in the pipeline which we are hoping to see sooner rather than later,” says Williams.

“Without a shadow of doubt, nuclear can become cost competitive, but we need to build more than one thing at a time.”

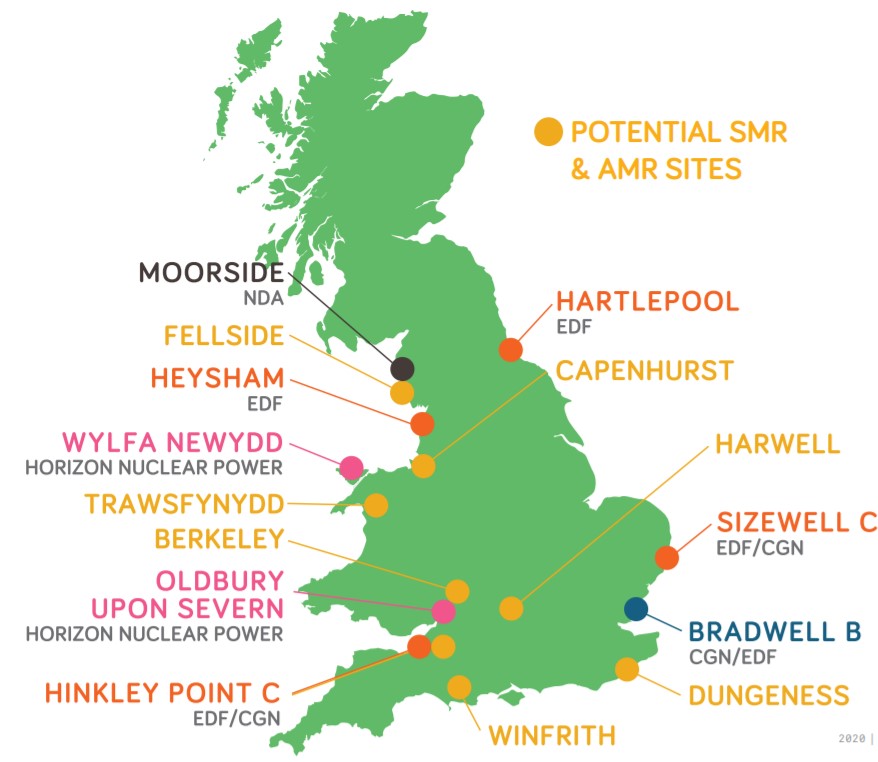

Nuclear new build sites (Source: Nuclear Industry Association)

Nuclear new build sites (Source: Nuclear Industry Association)

Hydrogen and District Heating

In ESC’s analysis, “Innovating to Net Zero”, bringing down the cost for nuclear reactors could be possible by coupling the plants with hydrogen production technology and deploying district heating (DH) in cities at scale while supporting a stage-gated development program for SMRs in parallel with Gen IV reactors.

A NIA study “Forty by ‘50: The Nuclear Roadmap” claimed that by 2050 nuclear can contribute up to 40% of the UK’s clean electricity with some 33 GW capacity while additional units coul support clean district heating and hydrogen production.

Nuclear energy currently supplies less than 20% of the UK’s electricity and demand is expected to quadruple over coming decades while much of the country’s current nuclear capacity comes offline.

New nuclear, including Gen III+, SMRs or Gen IV, will only be viable in the UK if the government commits to the necessary policies, say critics.

Policy issues which must be considered for further nuclear development include a support mechanism for easier access to capital, commitment to programs of capacity, rather than individual projects, stage-gated technology development programs for new technologies and clarity of markets for investors, such as DH and hydrogen supply, says ESC.

“What we have in the policy basket at the moment is fine to get us started, but for private sector investment there needs to be certainty that there’s a route delivering more,” says practice manager for nuclear at the ESC Mike Middleton.

By Paul Day